The « Association of Craftsmen, » was a collective of artists, architects, designers, and industrialists, tasked with lifting the local industry to new heights, both in quality and production numbers.

Image source:https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:100_Jahre_Deutscher_Werkbund_-_Postwertzeichen.jpg

Art Politics

To understand the Deutscher Werkbund, its birth, its means, and its goals, one first needs to understand the social, economical, and political context that led to its rise.

At the beginning of the 20th century, German industry strugged to maintain its power. Not only its most direct competitor, England, had surpassed it in both quality and volume of production, but America had also become a beacon of modern industry, thanks to its rising economy and technological innovation. In order to catch up, Germany incorporated traditional craftsmanship with the modern means of production to maintain artisanal quality and maximize its distribution. Further, their approach to the subject resonated with people.

Early Deutscher Werkbund

The first signs of interest towards such a proposal emerged in 1899, when the architect Joseph Maria Olbrich left Vienna for Darmstadt to form an artists’ colony at the invitation of Ernest Louis, Grand Duke of Hesse.

As such, in 1907, a collection of artists, artisans, designers, and architects founded the eponymous Deutscher Werkbund (its name meaning « Association of Craftsmen »), in Munich. Further, they shared goals of adopting architectural standardization as a form of art, mending the rift between industry and applied arts, and above all inspiring good design and craftsmanship for mass-produced goods and architecture. Additionally, the collaboration between twelve key figures and twelve business firms was also stressed.

From Two Points of View

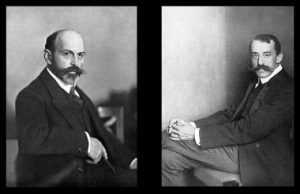

Heading the newly formed Werkbund were some of Germany’s most renowned professionals, such as Peter Behrens, Theodor Fischer, Josef Hoffmann, Bruno Paul, Max Laeuger, and Richard Riemerschmid. Two figures, in particular, became the de facto intellectual leaders. These are German architect Hermann Muthesius, “instigator” and founder of sorts together with Olbrich, and Belgian-born Henry Van de Velde. They both experienced the Arts and Crafts movement, proposing that industrial production is a collaborative effort. This principle Van de Velde and Muthesius expanded further upon to include machine-made goods. Also, they proposed that form be determined only by function and that ornamentation had to be eliminated.

These two personalities and their often opposing views eventually caused a split among the Werkbund ranks. Those who agreed with Muthesius’ ideas and who saw the association as a semi-official arm of the government of sorts, followed his advocation towards the greatest possible use of mechanized mass production and a renewed focus on standardized design. The other faction, championed the value of individual artistic expression instead. Further, this was in opposition to Muthesius’ growing interest in the streamlined, industrially produced in-series product.

Eventually, this “conflict” would come to an end once the Werkbund decided to adopt Muthesius’ approach, by 1914.

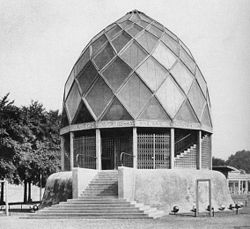

That same year, following the successful exhibit at the Parisian Salomn d’Autumne, the Werkbund rose to fame. Then, it further cemented its influence, by hosting an exhibition of industrial art and architecture in Cologne in 1914. The showcase held some notable examples of buildings in steel, glass, or concrete. Among these, are a theatre, garages and offices by Gropius, and a Pavilion by Bruno Taut.

Image source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Werkbund_Exhibition_(1914)

Beginnings and Ends

The Werkbund experience came to a halt at the beginning of World War I. They were forced in this state for the entire duration of the conflict and its aftermath. However, once the nation entered a new period of growth in the 20s, so did the Werkbund. Additionally, they reasserted themselves in the significant exhibition in Stuttgart (1927). Directed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, it was a compendium of contemporary European developments in commercial architecture and construction. Many of the exhibiting architects, such as Mies, Gropius, and even the famed Le Corbusier, followed the ideas of Muthesius. Further, they employed a high degree of standardization, in choices of materials and design making it possible to build housing units inexpensively.

Most notably, the exhibit showcased work of the Weissenhof estate, acting as a display for what would later become known as the International Style of architecture. This featured 21 buildings between terraced homes, detached houses, and apartments, and sixty dwellings. Despite this, variations are slight, and a strong consistency (simplified facades, flat roofs, and terraces, window bands, open plan interiors, elevated use of prefabrication, prevalence of the color white) is observable. Additionally, these homes were meant to be a prototype for future workers’ housing, although costs of production were still out of an average salary’s range.

Unfortunately, of the original 21 buildings complex, only half still survives today. The rest, irreparably damaged by World War II bombings, left nothing of the homes designed by Gropius, Hilberseimer, Taut, and Döcker. Further, two more would be demolished in the 50s.

Image source: https://www.internationale-bauausstellungen.de/en/history/1927-weisenhofsiedlung-stuttgart-a-testimony-to-neues-bauen/

After another exhibit in Breslau, in 1929, the association came to an end, as the Nazi party disbanded it.

However, after the end of World War II and the fall of the Nazi regime, the Werkbund resurfaced around 1949. They made their way into a brand-new world. Of the original Werkbund, most of its archived materials and collections are at the Museum der Dinge (Museum of Things), an institute dedicated to designs and everyday objects of the 20th-century life.

The Craftsmen’s Legacy

Even during its active period, the Werkbund and its ideas, a blending of traditional artisanship and modern industry, struck a chord with many other professionals. Similar organizations soon came to be, such as the Austrian Österreichischer Werkbund, in 1912. Further, the Swiss Schweizerischer Werkbund, in 1913, was created. Soon the converted, Swedish Slöjdföreningen and even British Design and Industries Association modeled itself after the Werkbund the same year.

However, one of Werkbund’s most visible imprints can be seen in the Bauhaus, the institute for the formation of future artists, architects, and designers. In addition, its history traces back to one of the Werkbund’s very members, Peter Behrens.

Behrens had already worked, within the Werkbund, for one of its main adherents, the AEG electricity company. His turbine factory, in steel and glass, not only had proven an exemplary modern edifice, answering to the Werkbund’s principles of building standardization, but also introduced various notable concepts of modern design. This included the coordinated image, the repetition of structural pattern, and Beherens’ identification of the building as a « monument. »

Under Behrens, many members of the Werkbund learned their trade. Van Der Rohe and Gropius, founders and key members of the Bauhaus school, among them. After their experiences within the Werkbund, these figures carried the same principles – standardization and industrial production, without sacrificing quality or personal touch – in their new enterprise.

Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Berlin_AEG_Turbinenfabrik.jpg

Info sources:

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Deutscher-Werkbund

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deutscher_Werkbund

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Weissenhof_Estate

https://www.fotoartearchitettura.it/architettura-contemporanea/deutscher-werkbund-bauhaus.html