Transcendentalist philosophy says that humans and nature are equal forces of the Earth, meant to coexist in harmony. Organic Architecture, created by Frank Lloyd Wright, embodies such principles, by creating a sustainable ecosystem of the natural and built environment.

Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Goetheanum_Dornach2.jpg

The Space Must Flow

Although musings over the blending of man-made housing and surrounding landscape existed for a long time, it is only in the cryptic notes left behind by legendary architect Frank Lloyd Wright that we first see the term “Organic Architecture”:

So here I stand before you preaching organic architecture: declaring organic architecture to be the modern ideal and the teaching so much needed if we are to see the whole of life and to now serve the whole of life, holding no traditions essential to the great TRADITION. Nor cherishing any preconceived form fixing upon us either past, present, or future, but instead exalting the simple laws of common sense or of super-sense if you prefer determining form by way of the nature of materials…

Frank Lloyd Wright

Wright committed to defining, and systematically incorporating in his style, the features of a new architecture style. This built upon the lessons of his mentor, Louis Sullivan.

Taking after his teacher’s tenet of « form following function, » Wright decided to take it a step forward, believing both elements were meant to be equally fundamental in a project. Thus, the new principle, upon which organic architecture rests is « Form and function are one. »

Organic Architecture Style Characteristics

The new expression has a number of defining characteristics. Most importantly, the core concept that buildings are to be likened to living organisms, and have to grow from within the environment and adapt to it. This resulted in structures that appeared “molded” from the same matrix as the surrounding environment, and colored with soft, fields and woodland-themed palettes.

However, one should not confuse organic architecture for a mere aesthetic, or an architecture in an organic shape. Organic architecture was born as a critical stance on traditional functionalism. While it embraces some core structural concepts, it rejects ideological basis, the glorification of machinery and standardization to pave the future. Simplicity and free flow of space are key to construction. Rooms are replaced by open spaces, while doors and furnishings take on practical and aesthetic functions alike. Overall, each building’s style is meant to suit the personality of its associated owner. Often these pieces defied standardization by giving each design its own unique charm.

Wright sought independence from classicist constraints, preferring a flexible, free interpretation approach to better reach harmony in the final project. It is recognized in Wright’s plans for prairie houses. It is shaped by its future inhabitants and its surroundings alike, striving for an equilibrium between the artificial and natural.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/69453be7-8805-437a-85af-f6799ec63cb4 by pabsanch

Organic Growth

While Wright is the most well-remembered author of Organic Architecture, he was far from the only one. Even among his peers, similar or complementary views to his own had already begun spreading, in The United States and Europe alike.

Key architects included Louis Sullivan, Claude Bragdon, Eugene Tsui, and Paul Laffoley in the United States, whereas in Europe there was Hugo Häring, Hans Scharon, and Rudolf Steiner. Others, like Wright’s former collaborators Rudolf Schindler and Richard Neutra, the creator of the well-known Lovell Health House in Los Angeles, traced their own path from Wright’s teachings, culminating with the creation of the “bio-realism” theory. In Italy, historian and critic Bruno Zevi contributed to the spread of Wright’s ideas throughout all of Europe.

Alvar Aalto

However, the most relevant of these figures is Alvar Aalto, a Finnish architect and designer, well known for his individualist and genre-breaking approach that differed from Wright’s. As such, Aalto’s interest in the habitat, its more or less artificial nature, stemmed in part from a desire to reaffirm Finnish/Scandinavian traditions and identities. Further, this contrasts with Wright’s approach of « refunding his native country. »

Aalto even more staunchly opposed the industrial mechanization than Wright. Often, he preferred the usage of traditional materials (woodwork, bricks…) over modern ones. Moreover, he had a tendency to freely innovate and mutate the flow of his project’s parameters. He also took into account elements overlooked by a Functionalist methodology. These elements included solar light, solar heat, ventilation, acoustics, and the identity links between the house and its occupants. Projects such as the Viipuri Library and the Paimio Sanatorium are a testament to such care.

Additionally, Wright and Aalto, each represented a side of the world, and are the initiators of this new conception of architecture, which contributed to a free-flowing exchange of ideas between the Old and New world.

Image source:https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/04ff5048-39b7-47d7-a1f9-fd60b5017765

Between Nature and Man

Architect and planner David Pearson formulated a list of rules meant to encapsulate the rules of organic architecture. They are the « Gaia Charter, » which required pieces must:

- Inspired by nature and be sustainable, healthy, conserving, and diverse.

- Unfold, like an organism, from the seed within

- Exist in the « continuous present » and « begin again and again »

- Follow the flows and be flexible and adaptable

- Satisfy social, physical, and spiritual needs.

- « Grow out of the site » and be unique.

- Celebrate the spirit of youth, play, and surprise.

- Express the rhythm of music and the power of dance.

Progression Over Time

Organic architecture is present during the entire design process, from windows to floors, furniture to spatial planning, and the reflecting the order of nature. The best example being the Fallingwater house.

Over time, the interpretations of organic architecture – thanks to the growing influx of creative talent – have become more varied. Some consider its core to be the connection between interior and exterior space. However, others locate it in planning abstract plant geometries, or in juxtaposing artificial forms within a natural environment. Additionally, some hold Wright’s vision of interpenetrating contrasts and volumes.

Organic Architecture Today

Today, organic architecture still thrives, but now reshaped by the changes of the new world. According to Wright’s own philosophy, it is a means to answer the ongoing challenges of change, social, technological, and conceptual. As the world evolves so does organic architecture, removing the staticity that could otherwise make it obsolete. As such, buildings considered « organic » range on a large and diverse spectrum, incorporating themes and tenets from other ideologies as well. An example includes life as an informatics and cybernetic construct (as dictated by futurism), or embracing the bizarre, otherworldly shapes of Post Modern and deconstructivist styles.

Many hope that organic architecture may be a sustainable and the viable answer to the ever-increasing urbanization, gentrification, and deforestation characterizing modern cities.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/5fae718e-2166-4954-8f15-9b104371ae9a by Patrick Bombaert

A Jungle of Buildings

Spanning more than a century it’s no surprise that the catalog of Organic Architecture is as vast as it is varied.

Quite possibly the most beloved example is the Falling water House created by Frank Lloyd’s Wright’s. Wright designed Falling water for the Kaufmann family, in rural Pennsylvania. He placed it over a typical large site on a waterfall with a creek, which added to the suggestive environment a soothing sound of rushing water.

The horizontal striations of stone masonry with cantilevers of colored beige concrete blend with native rock outcroppings and the woodland environment.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/29502a08-adad-454f-85c5-509815e3dc2b by Roller Coaster Philosophy

Organic Architecture in the East

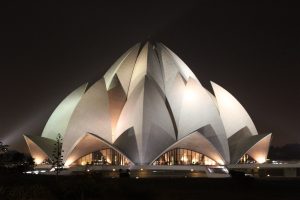

Organic Architecture spread in the East as well, taking root in India via the Lotus Temple. Built to evoke the homonymous flower, the edifice is a modern architectural wonder, born of Iranian-Canadian architect Fariborz Sahba’s designs. In accordance with the architectural principles stated by Abdu’l-Bahá, the building is a nine-sided circular shape made up of 27 freestanding marble-clad ‘petals’ arranged in clusters of three.

This Bahá’í House of Worship acts as a beacon of hope and harmony to its maker’s eyes:

Out of the murky waters of our collective history of ignorance and violence, mankind will arise to inhabit a new age of peace and universal brotherhood.

Fariborz Sahba, the temple’s creator.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/f73b55d8-89e3-49b3-a186-31240991c4c3 by Arian Zwegers

Other European Examples

Moving back to Europe, Organic Architecture could not be absent from Antoni Gaudì’s body of work. The extravagant Catalan architect, artist, and maker of bizarre, almost oniric buildings, experimented with the subject through Casa Mila. Also called “La Pedrera” (“The Stone Quarry”), the structure’s undulated, somewhat drooping edges bring to mind warm, melting wax, or gentle sea waves. Further, its odd proportions reference natural, « holy » geometries. The building receives the special mention of being among the oldest in the genre, dating back to 1912.

Combined with its roof, filled with chimneys, skylights, fans, and staircases, all of which stand as sculptures on their own, Casa Mila looks like a dream world.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/6d4adbf5-2d42-4884-9e7e-645c0d4e731a

Moving back into modern times, one of Austria’s most oddly striking buildings is the Kunsthaus Graz, located in the eponymous city of Graz. Fashioned after a giant slug slithering through the classical buildings, the Graz Art Museum is one bold example of organic architecture. Nicknamed « the friendly alien » due to its « skin » of iridescent blue acrylic panels, the building aims to be subversive and integrated within the cityscape. It does this by striking a dramatic contrast with the surrounding baroque roofs of its ‘host city’ with its red clay roofing tiles and integrating the façade of an 1847 iron house.

Image source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/marc_smith/1340840125

The « Gherkin » is not only one of London’s most peculiar architectural pieces, but it is one of the best examples of modern Organic style that is still relevant. Nominated as “best-loved tall building” of London, this pickle shaped building isn’t a mere exercise in aesthetic. Instead, it is true to its architecture’s harmony-oriented roots, and the Gherkin’s peculiar shape helps it conserve energy, reduce wind resistance and thus increase sustainability.

Image source:https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/5bd7c99e-d439-4f2f-85fe-2c59616567b8

Info sources:

https://www.domusweb.it/en/movements/organic-architecture.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Organic_architecture

https://impakter.com/organic-architecture-reinterpreting-the-principles-of-nature/

https://www.escooh.com/en/architettura-organica/che-cose-larchitettura-organica/

http://www.designcurial.com/news/organic-architecture—11-best-buildings-4540983