“Once I discovered architecture as a need of my nature, then that enthusiasm knew no bounds…art is the only thing I’ve been alive for. There’s no such thing as leisure time. If your work is architecture, you work all the time. You wake up in the middle of the night. ‘I’ve got a wonderful idea!'” Philip Cortelyou Johnson, American architect.

Image source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Johnson#/media/File:Philip_Johnson,_Esq.,_April_10,_1963.jpg

About his life

Philip Johnson, born Philip Cortelyou Johnson July 8, 1906, in Cleveland. Growing up in his home state of Ohio, Johnson’d attend the Hackley School at Tarryton, before becoming an undergraduate at Harvard University; during this period, his studies focused on Greek literature, philology, history and philosophy, especially around the Pre-Socratic period. Completing his studies in 1927, he started planning trips to Europe, developing an interest for historical Classical and Gothic monuments and buildings, being introduced, at the same time, to Modernism through architectural historian Henry-Russel Hitchcock.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/de4b1da4-fcee-413b-b92a-cc1ff8f754bf by Boston City Archives

In 1928, his meeting with legendary architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe would not only cement their lifelong friendship (and rivalry), but marked the beginning of his steadily rising fame as well.

By 1930, he joined the museum of modern arts, arraging for visits of European architects and designers (such as Gropius and Le Corbusier); this would last until 1936, when, due to the Great Depression, he left to venture into journalism and politics; this unfortunately led to his sympathy, and later full support, of the Nazi party and its zealotries; while some critics dismiss such political leanings as little more than a passing impulse (pointing to the help he offered to German architects fleeing their country, such as the aforementioned Gropius and Van der Rohe), it is undisputable that his fascist mindset had lasting consequences, both for himself and his businesses (it wasen’t until 2016 that a work by a Black architect or designer could be added to the Museum’s collections); despite abjuring these ideals in the latter decades of his life, many still were skeptical, believing him to still hold some of his worst convictions – making him an highly controversial figure to this day.

In 1946, after completing his military service, Johnson returned to the Museum of Modern Art, as curator and writer; it’s at this time that he began working on his Glass House, what would become his own private residence by 1949, inaugurating his Modern period, that would last all the way to the early 1980s, almost three decades; during this ouevre, his most recognizable projects would be the Seagram Building, a 39-stores skyscraper built in 1956 with Van der Rohe, the Lincoln center, the Boston Public Library, and the IDS center, the latter ones realized during his collaboration with John Burgee, beginning in the 1960s.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/3cba2ce7-f29b-45af-a6c7-078506304646 by Tom Ravenscroft

During the 80s, Johnson’s style underwent brisk turns and changes, starting with the eccentric megastructure known as Crystal Cathedral, a Neo-Gothic styled, skyscraper sized glass and metal church soaring through the heavens, placing him squarely in the Post-Modern movements of the time, soon followed by his signature AT&T building (later known as Sony building), and office complex Lipstick building . Often mixing styles and experimenting, Johnson’s career, either solo or with his historic collaborators (John Bungee first, and Alan Ritchie later on), until the 2000s, when, after retiring in the Glass house with his partner and lover, art curator David Whitney, until his death, in 2005.

Ultimately, Johnson’s role as an architect and critic is best focused on the promotion of the International Style and, later, for his role in defining postmodernist architecture, becoming, for all his controversies, one of America’s leading figures in design and architecture, for over 50 years.

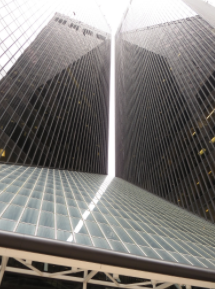

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/163562b6-1132-4320-adef-6651ef78160d by Mark B. Schlemmer

What are Johnson’s style main features ?

Throughout the 1930s, Johnson was pivotal in bringing the characteristically minimal aspects of the Modern style to the public. As both a writer and curator, he championed the work of many modern architects including Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, and Mies van der Rohe, displaying great interest in their aesthetic approach to structural elements . Their studies overtly addressed the role of the designer and builder, seeking to make the foundational elements of a building part of its aesthetic exterior.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/6932fe5f-02b0-4dfd-b619-af5d4292f9f8 by Mark B. Schlemmer

Johnson’s reputation was cemented by the design of his own residence, known as the Glass House, at New Canaan, Connecticut (1949), notable for its overly simple rectilinear structure and its use of large glass panels as walls, owed much to the precise, minimalist aesthetic of Van der Rohe, but also alluding to the works of 18th- and 19th-century architects.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/e079256b-9f40-44d3-a334-8932f0429b6f by Mark B. Schlemmer

In addition to the Glass House, Johnson’s New Canaan estate featured a number of other structures, including an art gallery and a sculpture pavilion. He later donated the estate to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and in 2007 it was opened to the public.

Images source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/5ce0881e-b24d-47f1-a33c-fe22a2a9b494 by Mark B. Schlemmer

This balance between Van der Rohe influences and historical allusions shifted in the 1950s. Beginning with the Temple Kneses Tifereth Israel in Port Chester, New York (1956), Johnson made fuller use of curvilinear (particularly arches) forms and historical quotation, a pattern continued in the art gallery at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C. (1963), and the IDS Center, a multibuilding group in Minneapolis (1973).

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/603581eb-0acc-42c8-a74b-d280e141490c by Sharon Mollerus

Other important works

- The Seagram Building, New York City, United States

- Pennzoil Place, Houston, Texas. Completed in 1975

- 550 Madison Avenue (formerly known as the Sony Tower, and before that the AT&T Building, New York City).

- Bobst library, New York City, United States

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/7bcd7085-444b-4dcd-a490-43aa24e43887 by Ken Lund

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/8e49fc14-6d34-4dfc-8709-fe46bacde5ac by Reading Tom

Info sources: