Built by famed architect Philip Johnson, this masterpiece is one of the nation’s greatest architectural landmarks. Inspired by Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House, the Glass House’s exterior walls are made of the omonymous material and with no interior walls, a radical representation of International Style ideals.

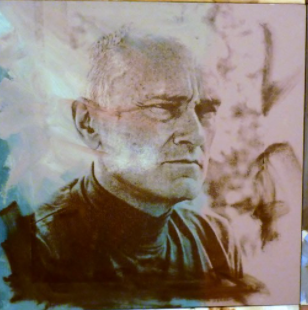

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/8458a6c5-6a4e-41f9-8c61-811b1a4544df by heldermira

Symbol of the International Style

Philip Johnson was a man of singular tastes, influencing architecture, art, and design during the second-half of the twentieth century. The house, which ushered the International Style into residential American architecture, is still iconic to this day because of its innovative use of materials and its seamless integration into the landscape. It began as an odyssey of architectural experimentation in forms, materials, and ideas through the addition of many new “pavilions” and the methodical “sculpting” of the surrounding environment. Today, the campus is an example of the successful preservation and interpretation of modern architecture, landscape, and art.

…The only house in the world where you can see the sunset and the moonrise at the same time, standing in the same place.

– Philip Johnson

Inspired by Mies van der Rohe‘s Farnsworth House, the Glass House by Philip Johnson, with its perfect proportions and its simplicity, is considered one of the first most brilliant works of modern architecture. Johnson built the 47-acre estate for himself in New Canaan, Connecticut. The house was the first of fourteen structures that the architect built on the property over a span of fifty years.

The Glass House was a remarkable achievement at the time of its completion, in 1949, not to mention the first design Johnson built on the property. The one-story house sports a 32’x56′ open floor plan enclosed in 18-feet-wide floor-to-ceiling sheets of glass locked between black steel piers and stock H-beams that anchor the glass in place. Invisible from the road, the house sits on a promontory overlooking a pond, allowing the occupant to gaze at the woods beyond.

The clear glass panels create a series of lively reflections, merging even with the surrounding trees, and playing with the silhouettes of people walking inside or outside of the house, layering them on top of one another, allowing for ever-shifting images with each step taken around it.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/6932fe5f-02b0-4dfd-b619-af5d4292f9f8 by Mark B. Schlemmer

The interior of the Glass House is completely exposed to the outdoors, except for the a cylinder brick structure – with the entrance to the bathroom – on one side, and a fireplace on the other side. The floor-to-ceiling height is ten and a half feet and the brick cylinder structure protrudes from the top.

The only other spacial arrangements in the house, besides the bathroom, are discreetly put into place through low cabinets and bookshelves, making the house, if not for this devices, a single open room. This allows for free flowing ventilation from all four sides of the edifice, as well as making sure the indoors environment is amply – and naturally – lit.

The Museum

Today, the Glass House is a museum of architecture and art, and the original building still resides there as the complex’s heart. Johnson’s New Canaan estate featured a number of other additional structures, including an art gallery and a sculpture-dedicated pavilion. He’d later donate the estate to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and in 2007 it was opened to the public.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/2738805c-b02c-481e-83b0-3b65dc24f9dc

The museum stands on a 49-acre National Trust Historic Site, comprising a series of buildings, fourteen in total, surrounded by a magnificent landscape, all designed by Johnson with European 18th century gardens as reference, including beautiful ponds, creeks, knolls, and woods.

Buildings in the site include the aforementioned Glass House (1945-1949), whose design first came to be as a tribute to Johnson’s mentor Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the Brick House, also completed in 1949, the Pavilion in the Pond (1962), the Painting Gallery (1965), the Sculpture Gallery (1970), the Studio (1980), and Da Monsta (1995), a black and red building inspired by the works of Frank Stella, all of them naturally designed by Johnson himself.

Buildings and site

The site’s analysis begins with The Brick House, made in 1949: The Glass House and the Brick House can offer a lesson in contrasting styles and modus operandis. Designed at the same time as former, the Brick House was completed a mere few months before. A grassy court links the two buildings, ultimately conceived as a single composition. Both houses are fifty-five feet long; however, the Brick House is only half as wide at the Glass House, while still containing all the support systems necessary for the functioning of both buildings. As opposed to the transparency of the Glass House, brickwork almost completely encases the structure, with the only openings being comprised of circular windos, with the exception of the skylights, located at the rear of the building; according to Philip Johnson, this series of round openings alludes to Filippo Brunelleschi’s fifteenth-century Duomo in Florence.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/40b7e191-1197-4b32-9c42-03a257b7a9e2

Next comes The Pavillion in the Pond, coming at a later date in 1962: The Pavilion in the Pond is built out of pre-fabricated concrete arches and roof sections, on a poured concrete base. The outdoor pavilion is sited at the edge of an artificially dug pond, located at the bottom of a hill below the Glass House. In the tradition of architectural follies in garden design, the Pavilion’s scaled down size plays with the viewer’s sense of perspective, making it seem further away than it actually is.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/163562b6-1132-4320-adef-6651ef78160d by Mark B. Schlemmer

Of note is The Painting Gallery, added by 1965: the building is located underground, with an entrance modeled after the Mycenean burial site known as Agamemnon’s Tomb. The paintings preserved inside are displayed on a system of three revolving racks of carpeted panels. Philip Johnson designed the Painting Gallery to house the collection of large-scale modern paintings that he and David Whitney accumulated throughout their lives. Works by Frank Stella, Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, David Salle, Cindy Sherman, and Julian Schnabel are represented in the permanent collection held in this building.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/aff02057-18de-4220-85e6-412b8b294b91 by Mark B. Schlemmer

Similar is the sculpture gallery, 1970 : Philip Johnson’s inspiration for this piece was, in part, the Greek Islands and their many stairways – characterized villages. The building’s plan comprises a series of squared shapes, set at 45-degree angles to each other. Staircases spiral down past a series of bays, each containing sculptures in the following visual sequence: Michael Heizer, Robert Rauschenberg, George Segal, John Chamberlain, Frank Stella, Bruce Nauman, Robert Morris, and Andrew Lord.

The building’s glass ceiling is supported by tubular steel rafters, lit by cold cathode lighting tubes; when hit by sunlight, it reveals an extremely complex pattern of light and shadows, forming in the building’s interior five levels. The structure so pleased Johnson that he seriously considered moving his residence from the Glass House to the Sculpture Gallery. However, he did not, stating “Where would I have put the sculptures?”

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/5ce0881e-b24d-47f1-a33c-fe22a2a9b494 by Mark B. Schlemmer

Finally, the studio, added in 1980 : a one-room workspace and library, was referred to by Johnson as an “event” on the landscape. The interior walls are lined with bookcases filled with 1,400 volumes on architecture, from nineteenth century tomes on German architecture to more recent publications on the work of Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, and J.J.P. Oud. The selection of books demonstrates the scope of Johnson’s architectural interests, from broad surveys of European, Japanese, Islamic, American, and ancient architecture to monographs on contemporary architects.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/ac1a49c7-1401-4c40-bd35-48da76fcf8e1 by Mark B. Schlemmer

One curious, last addition to the complex is Da Monsta, dating 1995 : Philip Johnson was a friend and supporter of both Frank Gehry and Peter Eisenman – the influence of both evident in the non-Euclidean planes of Da Monsta. However, Johnson claimed that his original inspiration for Da Monsta came from the design for a museum in Dresden by artist and friend Frank Stella. This building, constructed of modified gunnite, is the closest to Johnson’s thinking about sculpture and form at the end of his life – what he called the “structured warp.” This architectural direction using warped, torqued forms is far from the rectilinear shapes of the International Style.

The name of the building is an adaptation of the “monster,” a phrase for the building that resulted from a conversation with architecture critic Herbert Muschamp. Johnson felt the building had the quality of a living thing.

Image source: https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/archived/bydesign/da-monsta/3109498

Info sources:

http://theglasshouse.org/explore/brick-house/

http://theglasshouse.org/explore/pavilion-in-the-pond/

ttp://theglasshouse.org/explore/sculpture-gallery/

http://theglasshouse.org/explore/studio/

http://theglasshouse.org/explore/da-monsta/

https://www.archdaily.com/60259/ad-classics-the-glass-house-philip-johnson