Ancient Rome boasted impressive technological feats, utilizing many advances that would have been lost in the Middle Ages. These results would not have been rival until the Modern Age. Many practical Roman innovations have been adopted from previous designs.

The road to civilization

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/df21ae68-5401-47a5-87d5-e33ef0c96d6f by Pot Noodle

The Roman road system, was the transport network of the ancient Mediterranean world, extending from Britain to the Tigris-Euphrates river system and from the Danube River to Spain and North Africa. In all, the Romans built 50,000 miles (80,000 km) of a paved highway, mostly for military reasons.

The first of the great Roman roads, the:

- Via Appia (Appian Way), started by the censor Appius Claudius Caecusin 312 BCE, originally ran southeast from Rome 162 miles (261 km) to Tarentum (now Taranto) and was later extended to the Adriatic coast at Brundisium (now Brindisi).

- Via Popilia, a branch that crosses Calabria to the Straits of Messina

At the beginning of the 2nd-century BCE, four other major roads radiated from Rome:

- Via Aurelia, which extends north-west to Genua (Genoa); the Via Flaminia, which ran north towards the Adriatic, where it joined the Via Aemilia, crossed the Rubicon, and led northwest;

- Via Valeria, east across the peninsula through Lake Fucinus (Conca del Fucino);

- Via Latina, which runs south-east and joins the Via Appia near Capua.

Their many connection roads extending to the Roman provinces have led to the proverb “All roads lead to Rome.”

The Roman roads were notable for their straightness, solid foundations, rounded surfaces that facilitated drainage, and the use of concrete based on pozzolana (volcanic ash) and lime. They adapted their technique to the materials locally available and followed the same principles in building abroad that they had followed in Italy. In 145 BCE they began the Via Egnatia, an extension of the Via Appia beyond the Adriatic in Greece and Asia Minor, where it joined the ancient Persian Royal Road.

The system of roads outside of Italy

In North Africa, the Romans continued their conquest of Carthage by building a road system that spanned the southern shore of the Mediterranean. In Gaul, they developed a Lyon-centered road system, extending to the Rhine, Bordeaux, and the English Channel. In Britain, the strategic post-conquest routes were supplemented by a network radiating from London.

In Spain, on the other hand, the topography was characterized by a system of main roads around the periphery of the peninsula, with secondary roads developed in the central highlands. The Roman road system favored Roman conquest and administration and later provided highways for the great migrations in the empire and a means for the spread of Christianity. Despite the deterioration, it continued to serve Europe throughout the Middle Ages, and some fragments survive today.

Image source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Castle_of_Santa_%C3%80gueda

Construction techniques

The Viae were distinguished based on their public or private character and also based on the materials used and the methods followed in their construction. Ulpian divided them as follows:

- Via terrena: A plain road of leveled earth.

- Via glareata: An dirt road with gravel ground.

- Via munita: A street of regular construction, paved with rectangular blocks of stone, or with polygonal lava blocks.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/a2cf0365-1f74-4a62-aef9-18ea949de562 by Allie_Caulfield

The Romans are believed to have inherited from the Etruscans the art of road building which grew as it went along and incorporating good ideas from other cultures.

After the architecti surveyed the site of the proposed road and determined where it should go, the agrimensores set to work inspecting the road surface using two devices, the rod, and the groma, which helped them get right angles.

The gromatici, the Roman equivalent of rodmen, placed rods and laid a line called the rigour. Since they had nothing like a transit, an architect looked along the rods and ordered the gromatici to move them as needed to achieve straightness. Using the gromae they drew a grid on the street level.

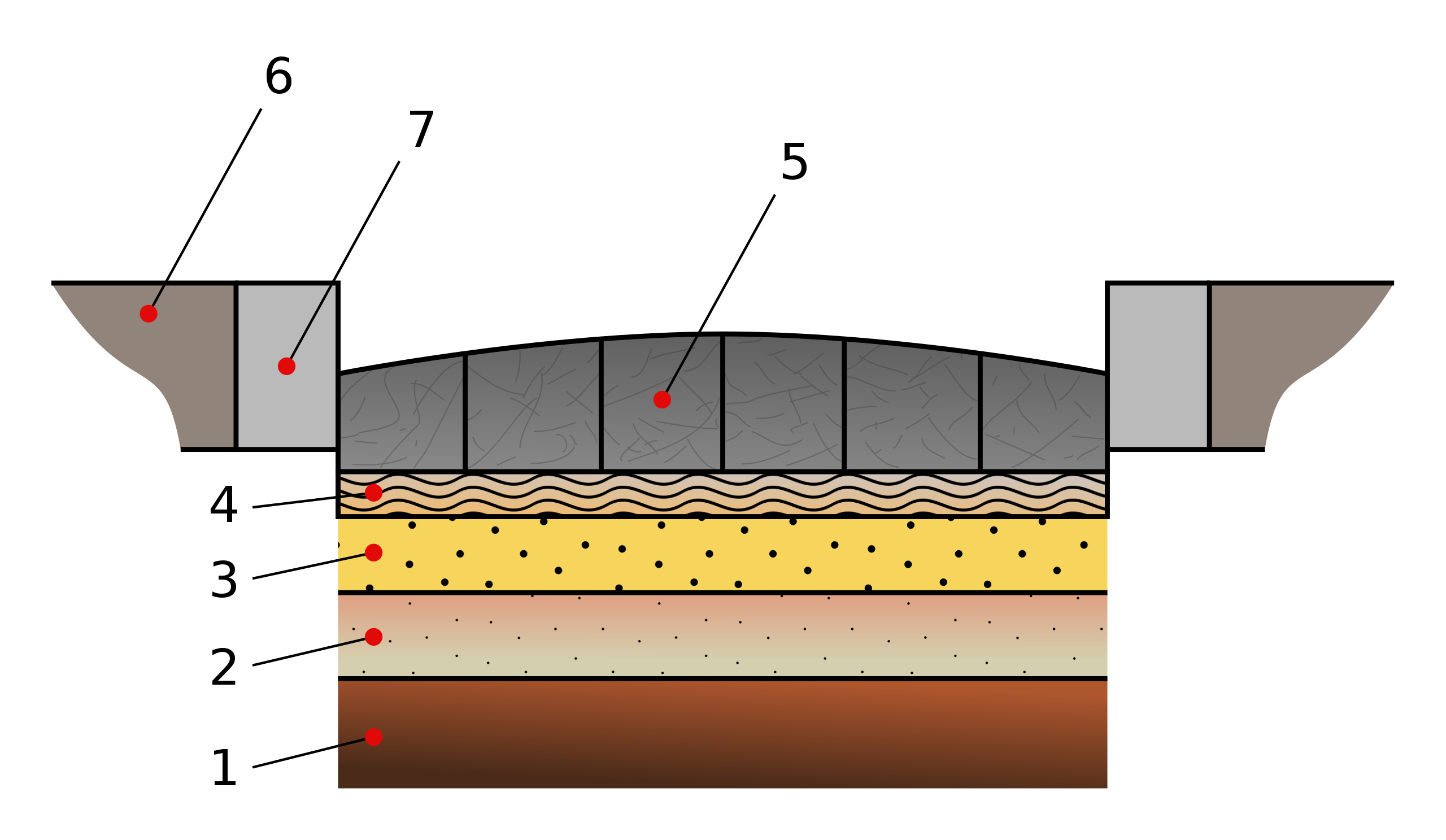

The libratores started their work. Using ploughs and legionaries with spades, they dug the roadbed down to bedrock or at least the most solid ground they could find. The excavation was called the fossa, “ditch.” It was typically 15′ below the surface, but the depth could vary based on the terrain. The road was built by filling the ditch. The method varied according to the geographic locality, the materials available, and the terrain. The roadbed was layered.

Large quantities of rubble, gravel and stone, were discharged into the pit. Sometimes a layer of sand was laid if it could be found. When it came within a few feet of the surface it was covered with gravel, and pounded, a process called pavire, or pavimentare. The flat surface was therefore the pavimentum. It could be used as the road, or additional layers could be built. A statumen or “foundation” of flat stones set into the cement could support the additional layers.

The last few steps used concrete by mixing the mortar and the stones in the fossa. First, a layer of rough concrete of several inches, the rudus, then a layer of fine concrete of several inches, the nucleus, went onto the pavement or statumen. Inside or above the nucleus passed a course of polygonal or square paving stones, called the summa crusta. The crusta was crowned for drainage. It is unclear whether standard terminology was used or whether it varies by region. An example is found on one of the earliest basalt street at the Temple of Saturn on Clivus Capitolinus. It had travertine flooring, polygonal basalt blocks, concrete bedding (substituted for gravel), and a rain-water gutter.

Image source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_roads#/media/File:Via_Munita_schema.svg

Today the concrete has worn away from the spaces around the stones, but the original surface was undoubtedly much closer to being flat. These extraordinary roads are resistant to rain, freezing, and flooding. They needed a little repair.

Roman architecti preferred to design solutions to obstacles rather than bypass them. River crossings were made by bridges or pontes. The individual slabs went over streams. A bridge could be of wood, stone, or both. Wooden bridges were built on stilts sunk into the river, or on stone piers. Larger or more permanent bridges required arches. The causeways were built on swampy terrain. The road was first bordered with pilings. Large amounts of stone were sunk between them to raise the causeway 6 feet above the swamp. In the provinces, the Romans used log roads (pontes longi).

Stone outcrops, ravines, or hilly or mountainous terrain required cuts and tunnels. Roman roads went straight up and down hills, rather than serpentine. Grades of 10%-12% are known in ordinary soils, 15%-20% in mountain villages.

Milestones

Image source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_roads#/media/File:Campidoglio_-_il_miliarium.JPG

Milestones divided the via Appia even before 250 BC in numbered miles and most routes after 124 BC. The modern word “mile” comes from the Latin milia passuum, “thousand steps”, which amounted to 4,841 feet (1,480 m). A milestone, or miliarium, was a circular column on a solid rectangular base, placed more than 2 feet (60 cm) in the ground, 5 feet (1.50 m) high, 20 inches (50 cm) in diameter, and about weight more than 2 tons. At the base was inscribed the number of the mile relative to the road on which it was located. A panel reported the distance from the Roman Forum and other information on the officers who had intervened on the road and when. These miliaria are now valuable historical documents. Their inscriptions are collected in volume XVII of the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum.

The aqueduct

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/001f3a26-fa92-4e2b-87c5-39a3c4475a3f by Andy Montgomery

An aqueduct is a water supply or waterway built to carry water. The word comes from the Latin aqua (“water”) and ducere (“to lead”). The Romans built aqueducts to bring a constant flow of water from distant sources into cities and towns. Wastewater was removed from sewage systems and released into nearby water bodies, keeping cities clean. Some aqueducts also served water for extraction, processing, production, and agriculture.

Rome’s first aqueduct provided a fountain located at the city’s livestock market. In the 3rd century AD, the city had eleven aqueducts, to support a population of over 1,000,000 in an economy rich in water resources; most of the water supplied the many public baths in the city. Most of the Roman aqueducts proved to be reliable and durable; some are still partly in use. The methods of survey and construction of the aqueduct are given by Vitruvius in his work De Architectura (1st century BC). General Frontinus gives more details on the problems, uses, and abuses of the public water supply of Imperial Rome. Notable examples of aqueduct architecture include the supporting pillars of the Aqueduct of Segovia and the aqueduct-fed cisterns of Constantinople.

What were the detection tools?

Image source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_aqueduct#/media/File:Esquilino_-_acquedotto_Anio_Vetus_1000968.JPG

To achieve a steady, shallow slope to move water in a continuous stream, the Romans laid underground pipes and built siphons throughout the landscape. Workers dug winding canals in the subsoil and created networks of water pipes to bring water from the spring lake or basin to Rome. The pipes were made of concrete but when possible they were made of lead a very expensive in 300 B.C. When pipes had to go through a valley, they built an underground siphon: a vast hollow in the ground that caused the water to descend so quickly that it had enough momentum to rise.

The problem with siphons, however, was the cost as they needed lead pipes for effective operation as the water had to pick up speed. This led to the use of arches, features often associated with Roman aqueducts. When siphons were impassable, arches were built to cross the valley. The pipes ran along the tops of the arches.

At some points along the route, the sedimentation tanks removed impurities from the water. In other sections, access points have been carved into the system so that maintenance workers can access the pipes. One way was to run two pipes next to each other and divert the water between the two so that men could enter one pipe at a time. The longest of the aqueducts, Anio Novus, was nearly 60 miles (97 km) long.

How were acqueduct bridges built?

The ducts could be supported through valleys or cavities on arches of masonry, brick, or concrete. The Pont du Gard, a massive multiple-hole Mansory conduit, also served as a road bridge. Where particularly deep or long depressions were to be crossed, inverted siphons could be used instead; here, the conduit ended in a collector that introduced the water into the pipes. These crossed the valley at a lower altitude, supported by a low “venter” bridge, ascended to a receiving tank at a slightly lower altitude, and discharged into another pipeline; the general gradient was maintained.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/427da4f4-d3f9-40da-a430-4ad890de27ee by MCAD Library

Siphon pipes were usually made of soldered lead, sometimes reinforced with concrete lining or stone sleeves. Less often, the pipes themselves were of stone or ceramic, tongue-and-groove jointed and sealed with lead. Vitruvius describes the construction of siphons and the clogging problems. However, siphons were versatile and effective when well constructed and well maintained. A horizontal section of high-pressure siphon pipe in the Gier aqueducts was raised on a bridge to clear a navigable river, using nine lead pipes in parallel, lined with concrete. Modern plumbing engineers use a similar technique to allow sewers and water pipes to pass through depressions.

The first system of sewers

The Romans had a complex system of sewers covered with stones, like modern sewers. The waste discharged from the latrines flowed through a central channel into the main sewer system and then into a nearby river or stream. However, according to Roman satirists, it was not uncommon for Romans to throw garbage from windows into the streets. Despite this, Roman waste management is admired for its innovation.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/3e2d8a6f-16c0-4f97-a1cc-759c745b23f3 by Jean-Pierre Dalbéra from Paris, France

It is estimated that the first sewers of ancient Rome were built between 800 and 735 BC. Drainage systems evolved slowly and began as a means of draining swamps and storm runoff. The sewers were primarily for the removal of surface drainage and groundwater. The sewer system did not take off until the arrival of the Cloaca Maxima, an open canal that was later covered, and one of the best-known sanitation artifacts of the ancient world. It is believed to have been built during the reign of the three Etruscan kings in the 6th century BC. This “largest sewer” in Rome was originally built to drain the flat land around the Forum. Over time, the Romans expanded the sewer system that crossed the city and connected most of it, including some manholes, to the Cloaca Maxima, which flowed into the Tiber River. The Cloaca Maxima was built in the 4th century BC and was largely rebuilt and closed under Agrippa’s authority as an aedile in 33 BC. It still drains the Roman Forum and surrounding hills.

Public and private latrines

Around AD 100, direct connections of the houses to the sewers began, and the Romans completed most of the infrastructure of the sewage system. Sewers were laid throughout the city, serving the public latrines, some private ones, and for homes not directly connected to a sewer system. They were mainly the wealthy whose homes were connected to the sewers.

In general, the poorest residents used pots that they should have emptied into the sewer or visited public latrines. The public latrines date back to the 2nd century BC. And have become places for socialization. Long bench seats with keyhole-shaped openings cut into rows offered little privacy.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/52b3ec18-b2ca-4844-90d3-ae1f99e1b056 by shankar s.

Image source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_toilet#/media/File:Ostia-Toilets.JPG

Recycle system

The Romans recycled the wastewater from public toilets using it as part of the flow that drained the latrines. Terra cotta pipes were used in the plumbing that carried wastewater from the houses. The Romans were the first to seal concrete pipes to withstand high water pressures. Beginning in the 5th century BC, city officials called builders oversaw health systems and were responsible for the efficiency of drainage and sewage systems, street cleaning and paving, odor prevention, and general supervision of brothels, taverns, baths, and other water supplies.

In the 1st century AD, the Roman sewer system was very efficient. In his Natural History, Pliny noted that of all the things Romans had accomplished, the sewers were “the most remarkable things of all”.

Info sources:

https://www.britannica.com/technology/Roman-road-system

http://www.crystalinks.com/romeroads.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_roads

https://www.britannica.com/technology/aqueduct-engineering

http://www.crystalinks.com/romeaqueducts.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_aqueduct

https://www.britannica.com/technology/sewer

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sanitation_in_ancient_Rome

http://science.howstuffworks.com/environmental/green-science/la-ancient-rome1.htm