Schists are a type of metamorphic rock and a fossil nature, meaning that at least one of the minerals in the rock crystallizes in platy form. The word schist comes from a Greek word meaning “to split”, in fact, schists usually split along parallel layers.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/6562acb3-1209-45a7-97f0-083ad7d98fdc by James St. John

What is a schist?

Schist is a foliated metamorphic rock composed of plate-shaped mineral grains. It usually forms on a continental side of the plate boundary where sedimentary rocks are subjected to compressive forces, heat, and chemical activity.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/914c5a08-a1e4-4c57-90c9-20817732de7c by Grand Canyon NPS

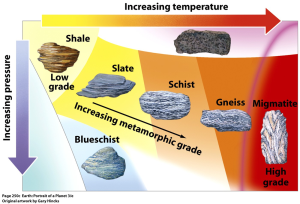

To become schist, a rock must be metamorphosed in steps through slate and then through phyllite. If the schist is metamorphosed further, it might become a granular rock. Rock to be called “schist”, only needs to contain enough platy metamorphic minerals in alignment and to exhibit distinct foliation.

Image source: http://geologycafe.com/class/chapter10.html

How Schists are Formed?

Schists are produced by intense pressure, formed by regional metamorphism, for this reason, they are linked with tectonics and mountain building events. Schists are found in regions such as the Central Alps, the Himalayas, Scandinavia, the Highlands of Scotland and northwest of Ireland.

The depth of burial and the amount of heat and pressure determines the type of metamorphic changes that the rock goes through. Two important categories are: the greenschists and the blueschists. These have similar parent rocks but are formed under different pressure (P) and temperature (T) conditions. So Greenschists form under high P and high T while blueschists form under high P and relatively low T.

Regional metamorphosis often happens at subduction zones, those settings where one tectonic plate is being driven edgewise into the mantle under another. If the mass stays down long enough to achieve both high T and high P produced greenschist, while one that returns to the surface relatively quickly produced blueschist. One of the unresolved puzzles of modern geology is that blueschist formation seems to have become globally more common in the last 300 million years.

Image source: http://scienceandminerals.weebly.com/metamorphic-rocks.html

Schist Types and Compositions

Schists are classified into different types of rocks. The two major groups are: parachutists, which are derived from sedimentary rock like shale, and orthoschists, which are metamorphosed from igneous rock. Schists are commonly classified base on their preponderant mineral composition. They are often a mix of quartz, feldspar, mica, and sometimes amphibole.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/0b7d78f8-3831-4660-a412-2ceb19e2ef88 by James St. John

The color of the schist depends mainly on its predominant minerals. Generally, schists may be gray, yellow, green, brown, white, or black. A separate group is that rich in quartz with variable amounts of white and black mica, garnet, feldspar, zoisite, and hornblende.

There are Schists of igneous origin that including the silky calc-schists, the foliated serpentines, and the white mica-schists.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/0191a7dc-dc2e-42df-9cb9-4d136d81bb97 by James St. John

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/12a7f8ee-070d-4e12-b9c9-2bc7d17afe19 by James St. John

Lots of mica-schists are altered clays and shales, and pass into the normal sedimentary rocks through various types of phyllite and mica-slates. They are among the most ordinary metamorphic rocks.

A special subgroup consists of the andalusite-, staurolite-, kyanite-, and sillimanite-schists which have probably been subjected to contact alteration. The more coarsely foliated gneisses present a wide variety differing in composition and appearance. They contain quartz and usually mica, often garnet, iron oxides, and so forth.

There are also other gneisses, derived from feldspathic sandstones, grits, arkoses, and sediments of that type. They contain mainly biotite and muscovite.

Image source: http://www.sandatlas.org/schist/

Where can we find Schists today?

Schists are often used in jewellery and other types of artwork.

They are quite strong and durable, which is why they have been frequently used in building houses or walls. In fact, most of the building foundations built between the 1920s and ’30s in the New York City area were made by schist. Decorative rock walls on houses in the area also used schist called “Yonkers Stone“, which is no longer available; this schist was particularly hard.

Moreover, some buildings at Princeton University and the University of Pennsylvania were constructed using this rock.

Schist does not have numerous industrial uses. Due to its low physical strength, the schist is unsuitable in construction aggregate, building stone, or decorative stone.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/d63faa6b-5c76-4484-91a4-6e6508a1f8d9 by Grand Canyon NPS

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/9cfbeb44-6672-4f9d-94c2-5108ebc33e17 by sybarite48

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/3ef9974a-03cd-4c83-a5ba-0ffc9f302b09 by pedrosimoes7

Info sources:

http://geology.com/rocks/schist.shtml