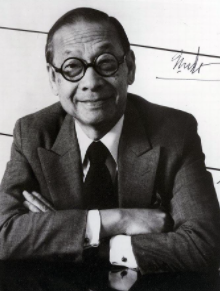

One of the most celebrated and prolific architects of our time. Pei has designed some of the most iconic buildings and extensions around the world and has won numerous awards for his unique modernist architectural vision.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/6a8340d7-843d-4f0e-8eca-35c2d8c2f171 by 準建築人手札網站 Forgemind ArchiMedia

“It is good to learn from the ancients,” says IM Pei with a smile. “I’m a bit of an ancient myself. They had a lot of time to think about architecture and landscape. Today, we rush everything, but architecture is slow, and the landscapes it sits in even slower. It needs the time our political systems won’t allow.”

Impeccably mannered and quietly spoken, Pei, now 101, has walked an architectural tightrope for half a century. Marrying ancient and modern, he has created buildings as influential as the trapezoid-shaped east wing of Washington’s National Gallery of Art, as ambitious as the Bank of China’s soaring HQ in Hong Kong, and as controversial as the Pyramide du Louvre in Paris. He has won pretty much every prize his profession has to offer.

Info source: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2010/feb/28/im-pei-architecture-interview

Biography

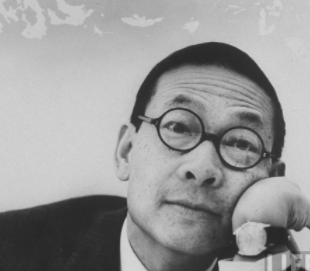

Born Ieoh Ming Pei on April 26, 1917, in Canton, Guangzhou, China, I. M. Pei is one of the world’s most famous architects. When he was 17 years old, he traveled to the United States, initially attending the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia before transferring to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in architecture in 1940.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/71aebb08-6f45-4e83-92f8-212a2634c6b5

Pei soon continued his studies at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, where he had the opportunity to study with German architect and founder of the Bauhaus design movement Walter Gropius. During World War II, Pei took a break from his education to work for the National Defense Research Committee. In 1944, he returned to Harvard and earned his master’s degree in architecture two years later. Around this time, Pei also worked an assistant professor at the university.

In 1948, Pei joined New York-based architectural firm Webb & Knapp, Inc., as its director of architecture. In 1955 he left to start his own firm, I. M. Pei & Associates (now known as Pei Cobb Freed & Partners). One of his first major projects was the Mile High Center in Denver, Colorado. Pei also devised several urban renewal plans for areas of Washington, D.C., Boston and Philadelphia around this time.

Image source: http://www.photohome.com/photos/colorado-pictures/denver/mile-high-center-1.html

Pei continued to design impressive buildings during the 1990s, including the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/770e32d9-dd13-44fc-a651-b74add0ca23f by laszlo-photo

For more than 60 years, Pei has been one of the world’s most sought-after architects and has handled a wide range of commercial, government and cultural projects. He created the Musée d’Art Moderne in Kirchberg, Luxembourg, completed in 2006.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/f5c317e7-dbe3-4300-8c4d-59f8861453de by myahya

Now he his 101, Pei still maintains an active work schedule. In India, he has several designs in process, including Mumbai’s Lodha Place. He is also working on Los Angeles’s Century Plaza, Fordham University’s Lincoln Center Campus in New York and the Charles Darwin Centre in Darwin, Australia.

Info source: https://www.biography.com/people/im-pei-9436323

Major projects.

- Louvre Crystal Pyramid: Pei’s most well-known work worldwide is probably his underground extension to the Louvre in Paris, including the crystal pyramid. It is one of many that adopt a ‘futuristic’ vision, brutally breaking from tradition. Originally a point of controversy after its completion in 1989, the pyramid has been accepted over the years and is now hailed as one of his most iconic projects. Pei said: “Formally, [the pyramid] is the most compatible with the architecture of the Louvre … , it is also one of the most structurally stable of forms, which assures its transparency, as it is constructed of glass and steel, it signifies a break with the architectural traditions of the past. It is a work of our time.”

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/29963162-92d3-403f-a204-5528a13c4700 by dalbera

- The Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong: opened in 1990, was the tallest building in Asia until 1992 and is still one of the tallest in Hong Kong. At 70 stories high, the asymmetrical steel and glass tower holds strong symbolic meaning for the Chinese people and goodwill towards the British Colony. Inspired by bamboo, a symbol of hope and revitalization in China, the trunk of the building emulates the growth patterns of the plant, reducing its mass towards the top. The composite structural system also resists high winds and eliminates the need for many internal vertical supports, a usual requirement in the typhoon-prone location.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/6b230665-bf43-4300-a994-a0647cf2a6bc by Bernard Spragg

- The JFK Presidential Library (1979): Columbia Point peninsula in Boston has been said to exemplify an ‘architectural presence representing both memorial and monument.’ With Pei’s play of space and light, and his iconic geometric structures, the library’s understated form comprises a singular and brilliant triangular tower protruding from an expanding base of geometric forms, with a cube of glass and steel rising along with the tower.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/e48fd972-6cc4-4b6d-a1b0-5cd1f5f2fca1 by btwashburn

- The East Building of the National Gallery of Art (1978): in Washington DC was designed to reflect the trapezoidal form of the plot it stands on. Pei started from two triangular sections, and used the isosceles as a unifying motif of the building, in the marble floors, steel frame and glass skylights. Other triangular forms are repeated in a variety of elements, while the interior features softened, rounder lines. In the plaza between the East and West Buildings are glass pyramids referencing the East Building’s ceiling. The pyramids subsequently became a trademark of Pei’s museum designs, as seen in the Louvre.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/583d5290-70c8-4d04-ad9f-44c264d217bc by gnrklk

- Dallas City Hall: Completed in 1978, Pei’s Dallas City Hall was designed as an inverted pyramid, a reflection of the space requirements—small for the public-facing offices on the ground floor, large for the administrative offices above. The glassy design also literally reflected an image of the city and people entering the seat of government.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/fdb370db-d9af-471b-b2de-f69bc87ed751 by alexliivet

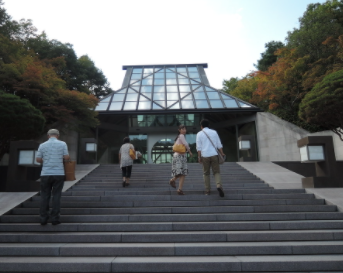

- Miho Museum: In the late 1990s, Pei traveled to Kyoto, Japan to design what would become his favorite project, the Miho Museum. Built to house the private collection of Mihoko Koyama, the museum features a tunnel entrance, soaring glass ceilings, and the same stone Pei used to line the Louvre lobby.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/c1efea57-fdf7-49db-8447-f553124b22bd by Yuya Tamai

Info source: https://www.curbed.com/maps/im-pei-buildings-works

Info source: https://theculturetrip.com/asia/china/articles/profiling-ieoh-ming-pei-china-s-best-known-architect/

Info source: https://theplanetd.com/top-5-architectural-wonders-of-i-m-pei/

Style and method

Pei’s designs represent an extension of and elaboration on the rectangular forms and irregular silhouettes of the prevailing International style. He is notable, however, for his bold and skillful arrangements of groups of geometric shapes and for his dramatic use of richly contrasted materials, spaces, and surfaces. Although Pei retired from his firm in 1990, he continued to design buildings, such as the museum in Doha, which extended his signature style to embrace elements characteristic of Islamic architecture in various eras.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/0ea0fcee-050d-47ac-8177-f9e4806c05ed by jikatu

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/5a0fd72b-8ece-4583-8409-c25983e4adf1 by 準建築人手札網站 Forgemind ArchiMedia

Info source: https://www.britannica.com/biography/I-M-Pei

Award and honors

In the words of his biographer, Pei has won “every award of any consequence in his art”, including the Arnold Brunner Award from the National Institute of Arts and Letters (1963), the Gold Medal for Architecture from the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1979), the AIA Gold Medal (1979), the first Praemium Imperiale for Architecture from the Japan Art Association (1989), the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, the 1998 Edward MacDowell Medal in the Arts, and the 2010 Royal Gold Medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects.

Architect I. M. Pei received one of the world’s most prestigious prizes for architecture, the Royal Gold Medal, at the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in London.

Image source: https://www.e-architect.co.uk/architects/i-m-pei-architect

In 1983 he was awarded the Pritzker Prize, sometimes called the Nobel Prize of architecture. In its citation, the jury said: “Ieoh Ming Pei has given this century some of its most beautiful interior spaces and exterior forms … His versatility and skill in the use of materials approach the level of poetry.” The prize was accompanied by a US$100,000 award, which Pei used to create a scholarship for Chinese students to study architecture in the US, on the condition that they return to China to work.

In being awarded the 2003 Henry C. Turner Prize by the National Building Museum, museum board chair Carolyn Brody praised his impact on construction innovation: “His magnificent designs have challenged engineers to devise innovative structural solutions, and his exacting expectations for construction quality have encouraged contractors to achieve high standards.” In December 1992, Pei was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George H. W. Bush.

Info source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I._M._Pei