French architect and designer Charlotte Perriand aimed for functional living spaces to help better society. In her article “L’Art de Vivre” from 1981 she states, “the extension of the art of dwelling is the art of living—living in harmony with man’s deepest drives and with his adopted or fabricated environment.”

Image source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlotte_Perriand#/media/File:Charlotte-perriand-au-japon-1954-4.jpg

Early Life

Perriand’s drawing abilities first caught the attention of her junior-high-school art instructor. At the urging of her mother, Perriand attended the École de l’Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs from 1920 to 1925. There, under the tutelage of the school’s artistic director, Henri Rapin, a talented and practicing interior designer, she thrived.

She attended lectures by Maurice Dufrêne, the studio director of La Maîtrise workshop, located at the Galeries Lafayette department store in Paris. Because of his association with the store, Dufrêne challenged the students with pragmatic, applicable projects, the results of which could be used by the Galeries Lafayette. Perriand’s schoolwork revealed her to be an adroit designer, and her projects were selected and exhibited at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes.

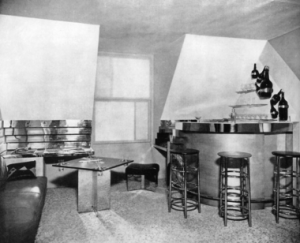

Image source: https://eyeondesign.aiga.org/charlotte-perriand-bar-attic/

After graduation, greatly encouraged by Dufrêne and Rapin, who had advised her that she “had to show to get known,” Perriand submitted her work to be displayed at numerous exhibitions. Her most-notable entry was in the year 1927, at the Salon d’Automne, with her design Bar sous le toit. This piece was an installation of furniture, finishes, and a built-in bar. With her use of materials such as nickel along with a bold design, Bar sous le toit revealed Perriand’s preference for an aesthetic that mirrored the age of the machine, which break with the École’s preference for finely handcrafted objects made of exotic and rare woods. Further, the project was a watershed moment in her career, as Perriand wholeheartedly embraced the use of steel, a medium previously used only by men.

Le Corbusier’s Influence

Perriand read Le Corbusier’s books, “Towards an Architecture” and “The Decorative Art of Today,” setting in motion her next endeavor: to work with the author. His writings “dazzled” her. By Perriand’s account, when she arrived at his atelier, with her portfolio in hand, seeking a position, he dismissively told her, “we don’t embroider cushions in my studio.” Not discouraged by his degrading comment, she invited him to the Salon d’Automne to view her work. Le Corbusier, finally recognized a kindred spirit after he saw her Bar sous le toit design and hired her.

Image source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlotte_Perriand#/media/File:Meubles_Charlotte_Perriand.JPG

From 1927 to 1937, she worked in the atelier, later calling that experience “a privilege.” Her charge and focus was on “the equipment of a modern dwelling,” or furniture designed by the atelier, including the fabrication of the prototypes and their final production.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/718a3bce-a7ef-429c-a275-4626a8ea2a04 by Tim Evanson

In 1928, she designed three chairs that followed Corbusier’s principles that the chair was a “machine for sitting.” Each of the three chairs accommodate different positions for different tasks. At Corbusier’s request a chair was made for conversation: the B301 sling back chair. Another made for relaxation: the LC2 Grand Confort chair. In addition, the last designed for sleeping: the B306 chaise longue. Moreover, the chairs had tubular steel frames, painted in the prototype models, but the production steel tubes were nickel- or chromium-plated.

Image source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlotte_Perriand#/media/File:Charlotte_perriand,_sedile_ruotante,_parigi_1927.JPG

Her presence in Le Corbusier’s studio is visible in all the furnishings, designed with him and with his cousin Pierre Jeanneret. Thus, Perriand became a cornerstone in the reformation project promoted by the architect as she added a distinctly human warmth to the often cold rationalism of Le Corbusier. In her creations she managed to animate the fundamental substance of daily life with new aesthetic values In particular, her talent and intuition in the discovery and use of new materials manifest themselves to their full extent.

The War and the Far East

Perriand abandoned her partnership with Le Corbuisier in 1937, seeking to strike out on her own. But the friendship and professional relationship forged with him, as well as the methodological principles and teamwork approach, would remain central to her practice. Additionally, at the beginning of the war, she researched the design of temporary, prefabricated housing with Jean Prouvé and Pierre Blanchon.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/67dc18a5-4c04-4051-a660-d5adcb422249 by dalbera

In 1940, she received an invitation from the Japanese ministry of commerce and industry to advise on the future of Japanese industrial art production. The Japanese reinforced her interest in the potential of artisanal processes and materials for new uses. During her long stay in the Far East (‘40-‘46), she revealed her artistic talent to the full, through a reinterpretation of the reality of life echoing both tradition and modernity. Worthy of mention are the furnishings produced using traditional bamboo processing techniques, which were capable of enhancing the new forms already experimented using steel-tubing. In addition, the famous chaise lounge, for instance, is bamboo.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/03faee54-e040-4065-8e7d-091bbaee3eb6 by dalbera

In her post-war practice, Perriand worked with a wide variety of peers, including Le Corbusier. With him, she designed the prototype kitchen for the first of the famous unités d’habitation. Also, she designd prefabricated kitchen and bathroom units, associated with Formes Utiles. This was an organisation committed to encouraging good design in mass-produced everyday objects for the domestic environment. Additionally, she designed offices for Air France in London and Tokyo, and studio apartments and fittings for the sports/hotel complex at Arcs en Savoie.

Women and Furniture Design

After World War I, women gained more opportunities than before, but they were still barred from many professions. For example, women attended the Bauhaus, but they did not study furniture making or architecture. Further, nearly all women were shunted to the weaving workshop. However, Perriand, bored by the traditional Beaux-Arts designs around her, hoped to design furniture using new industrial materials.

Image source: https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/a1167cfd-68df-4f36-9d88-828c061ebcc1 by Knowtex

Perriand successfully escaped the straitjacket of design traditionally designated as female. At her time women were expected to stay home and “embroider cushions.” However, Perriand bent tubular steel and traveled the world in search of a modern aesthetic. Although too often obscured by Le Corbusier’s fame, she designed some of modern furniture’s icons.

Charlotte Perriand’s full membership of the avant-garde movement began in the first decades of the twentieth century. She brought a profound change in aesthetic values and started a truly modern sensitivity towards everyday life. Her specific contribution to interior composition created a new way of living that is the heart of contemporary lifestyle.

Info sources:

https://www.cassina.com/en/designer/charlotte-perriand

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Charlotte-Perriand

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlotte_Perriand

https://www.theguardian.com/news/1999/nov/08/guardianobituaries

https://www.apartmenttherapy.com/last-week-we-discussed-98469